Network topologies and spectrum efficiency of High and Low Tower Broadcast Networks

Posted on June 3, 2014 Leave a Comment

I have made a study, comissioned by Broadcast Networks Europe (BNE), on network topologies and spectrum efficiency of High and Low Tower Broadcast Networks. The study is based on results from computer simulations made in a software that I created specifically for this work.

Below follows excerpts from the Executive Summary and Background sections in the final report of this study. The full report can be downloaded further down in the end of this blog post.

Existing terrestrial broadcasting networks are based on high power transmissions from high towers and masts. The high tower infrastructure is usually supplemented by in-fill transmitters using low to medium height towers to cover areas where the high tower transmissions do not reach, for instance due to terrain irregularities and shadowing. Additional sites are also sometimes needed to tailor coverage areas to deliver regional broadcast content.

Using high towers and masts is a cost-efficient solution to provide broadcasting services, i.e. where the same content is consumed simultaneously by a large audience over a large area. The higher the mast, the larger the coverage area, meaning that a limited number of high power transmitters can be used to cover very large areas and populations. In practice there is a limitation of the maximum height of a mast for technical and cost reasons. Most European countries use broadcasting masts and towers with heights in the range 150-300 meters to efficiently provide the required coverage. The optimal height depends on surrounding terrain, coverage requirements, cost considerations, the need for regional services and other national or local conditions.

For many years the broadcasting infrastructure was the only nationwide terrestrial infrastructure to provide radiocommunication services to the general public. However, when public mobile networks were rolled-out they were generally established using low tower infrastructures. The two main reasons were that mobile cell sizes are limited by the available output power of the handsets and that cell sizes need to be small enough to provide the necessary capacity to serve all active users in each cell.

Based on the almost universal availability of low tower infrastructure for mobile networks it has been suggested that this infrastructure may also be used for broadcasting purposes, possibly replacing the traditional high tower broadcasting infrastructure. A number of important issues will need to be analysed and addressed in this context. In this study two key aspects are considered; number of sites and potential spectrum gain;

for comparison of high tower (HT) based architecture with low tower (LT) based architecture for terrestrial broadcasting.

To investigate the feasibility of different network configurations for the transmission of digital terrestrial television (DTT), alternative network architectures with different power levels and transmitting antenna heights (300 m, 50 m and 30 m) have been studied for fixed reception with rooftop antennas. In all cases Single Frequency Network (SFN) design and DVB-T2 technology was used.

The full report can be read here.

–

Thank you for reading this blog post about Network topologies and spectrum efficiency of High and Low Tower Broadcast Networks. If you have any comments or questions don’t hesitate to contact me. All feedback is welcome!

The Importance of a Site Survey

Posted on April 13, 2014 Leave a Comment

In radio network planning projects it is more of a rule than an exception that the given site coordinates are inaccurate compared to the resolution of the underlying terrain database. If inaccurate input data is entered into the radio network planning software, the resulting output will also be inaccurate. Garbage in, garbage out!

The purpose of this blog post is therefore twofold: firstly, to describe why and under what conditions such inaccurate site locations might have a very profound effect on the important field strength calculations, and secondly, to clearly convince why a thorough site survey always should be conducted before starting the field strength calculations.

In radio network planning software the signal strength contribution from a specific transmitter is estimated by a radio propagation model on a regular grid of points. Usually, this grid will have the same resolution as the terrain elevation database used by the radio propagation model. As a consequence, each grid point can be seen as an area of corresponding size, for example 50 meter × 50 meter. These small areas are called pixels.

In strongly hilly and rolling terrain areas, where there are large height variations between adjacent pixels, an incorrect site location becomes particularly evident on the field strength calculation. This is best shown by an example:

A coverage map must be created for an existing transmitter using ERP 40 dBW and antenna height 15 meter. The provided site coordinates is unfortunately not that very accurate, see Figure 1 below. The figure presents a screenshot from PROGIRA® plan where the terrain elevation grid is indicated with squares that have a black coloured outline. Each square represents a pixel of size 100 meter x 100 meter. In the centre of each square the terrain elevation is presented in pink colour. A terrain height contour, where the distance between contour lines is 25 meter, has been generated from the terrain elevation grid and is presented in the map with the pink dash-dot-dot lines.

The given site location is indicated with a red cross and the interpolated terrain elevation height at this location is 1 629.9 meter. By visually examining the background map (Bing Maps) it is obvious that the correct site location instead must be at the location which is indicated with a green cross. At this location the interpolated terrain elevation height is 1 783.5 meter. Between these two sites, it is thus a height difference of more than 150 meter, and according to the Meaure tool the distance location error is almost 290 meters.

Figure 1: PROGIRA® plan screenshot. Terrain elevation grid is indicated with squares that have a black coloured outline. In the centre of each square the terrain elevation is presented in pink colour. The pink dash-dot-dot line represents a generated terrain height contour where the distance between contour lines is 25 meter. The given site location is indicated with a red cross and the adjusted site location is indicated with a green cross.

Figure 2 below presents a screenshot from Google Earth, where this site location error also can be studied. The red pin is the given site location and the green pin is the adjusted site location.

Figure 2: Google Earth screenshot. The red pin is the given site location and the green pin is the adjusted site location.

The incorrect given site location will of course have a great negative impact on the calculated field strength contribution. Because the given antenna height is only 15 meter it will be far below the top of the mountain and it is obvious that the field strength contribution to the eastern side of the mountain will be strongly damped.

In Figure 3 and 4 the field strength contribution for the two site locations are presented. The pink-purple colour represents areas where the field strength levels are above 87 dBµV/m, the dark blue colour represents areas where the field strength levels are above 77 dBµV/m, and the light blue areas represents areas where the field strength levels are above 53 dBµV/m.

–

Thank you for reading this blog post about the importance of conducting a site survey before starting the field strength calculations. If you have any questions about this post don’t hesitate to contact me. All feedback is welcomed!

How do you reach the full potential of your SFNs?

Posted on March 8, 2014 Leave a Comment

In large SFNs, where the transmitter separation distances exceed the selected guard interval length, self–interference zones might occur within the required service area. These zones might have a very strong negative impact on the network coverage probability. The network planner can apply several different approaches to mitigate the negative effect of the self–interference zones. The self–interference zones can for example be “moved” to areas outside the required service area by assigning thoughtful delays on the transmitters that builds up the SFN. Doing this manually is a tedious and time consuming process.

To help the network planner in this process PROGIRA® plan has been equipped with the SFN Optimization tool. This tool uses advanced optimization algorithms that automatically assign delays to the transmitter so that the self-interference zones are moved to areas with least impact on the population coverage.

Other parameters that can be optimized to mitigate the effects of the self-interference zones are: transmitter locations, transmitter powers, antenna heights, antenna patterns, antenna down tilting, polarization, etc.

An example where PROGIRA® plan SFN Optimization tool is used

In the following example a DVB–T2 network must be designed to provide indoor coverage with a bitrate capacity of at least 34 Mbit/s within the required service area. The required service area is 5 140 square kilometers and the population within this area is 143 950. To meet the capacity requirement the DVB–T2 system parameters presented in Figure 1 have been selected.

At our disposal we have eight (8) transmitters where the separation distances far exceed the selected guard interval. These transmitters can be divided into three different types of classes:

- Large: ERP 47 dBW, antenna height 300 meters;

- Medium: ERP 37 dBW, antenna height 75 meters;

- Small: ERP 34 dBW, antenna height 50 meters.

The SFN consists of one (1) Large, three (3) Medium, and four (4) Small transmitters. In the following coverage maps these transmitter classes can be identified by the size of the transmitter icons, the larger the icon the greater transmitter. All transmitters also use omni-directional antennas.

In Figure 2 and 3 the self-interference zones and the indoor coverage map is presented for the case when no delays have been assigned to the transmitters. The self-interference zones are significant, only 48% of the service area and 52% of the population meet the coverage requirement.

By using the SFN Optimization tool, and by only optimizing the individual transmitter delays, these self-interference zones have been removed, see Figure 4 and 5. We can conclude that the self-interference zones have been reduced significantly, 62% of the service area and 85% of the population now meet the coverage requirement. A significant improvement!

–

Thank you for reading this post regarding SFN Optimization and how to reach the full potential of your SFNs by using the tools in PROGIRA® plan. Please share and comment. All feedback is welcome!

Four (4) Important News in Rec. ITU-R P.1546-5

Posted on December 15, 2013 Leave a Comment

Rec. ITU‑R P.1546 is a notorious radiowave propagation model, used for point-to-area predictions for frequency and network planning of terrestrial services in the frequency range 30 MHz to 3 000 MHz. The latest version of this recommendation can be found here: http://www.itu.int/dms_pubrec/itu-r/rec/p/R-REC-P.1546-5-201309-I!!PDF-E.pdf

The first version of Rec. ITU‑R P.1546 was approved already in October 2001. The recommendation has then been updated continuously and the latest version Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5 was approved by ITU (International Telecommunication Union) in September 2013.

This blog post will present four (4) important news in Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. A number of comparisons to its previous version, Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑4 which was approved in October 2009, will also be presented.

Calculation procedure for distances less than 1 km (Changed)

The calculation procedure for distances less than 1 km between the transmitting and receiving antenna has been changed in Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. In Figure 1 the field strength values are presented for both Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑4 and Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5, for an all land path in the distance range 0.1‑250 meter. The field strength values are calculated for a frequency of 600 MHz, 50% of time, and a transmitting and receiving antenna height above ground level of 150 meter and 10 meter respectively. We can clearly see that for short distances there are large discrepancies in field strengths between Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑4 and Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. At the unreasonable short distance of only 0.1 meter, the deviation is as great as 42.9 dB. The differences then decline rapidly but at 150 meters the deviation is still as large as 2.7 dB.

Figure 1: Calculated field strength values using both Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑4 and Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5, for an all land path in the distance range 0.1‑250 meter, at a frequency of 600 MHz, 50% of time, where transmitting and receiving antenna height above ground level are 150 meter and 10 meter respectively.

Correction for clutter shielding the transmitting antenna (New)

Correction for clutter shielding the transmitting antenna is a new feature in Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. In Figure 2 the cluttered transmitter correction is presented for a transmitting antenna height above ground level range of 1‑35 meter, and at a frequency of 600 MHz, and for three different clutter heights above ground level in the vicinity of the transmitting antenna.

Figure 2: Cluttered transmitter correction for a transmitting antenna height above ground level range of 1‑35 meter, at a frequency of 600 MHz, and for three different clutter heights (R1) above ground level in the vicinity of the transmitting antenna.

Correction for difference in height between transmitting and receiving antenna (New)

Correction for difference in height between transmitting and receiving antenna is a new feature in Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. In Figure 3 the antenna height difference corrections are presented for a horizontal distance range of 0.1‑1.5 km between transmitting and receiving antenna, and for five different transmitting antenna heights above ground level, where receiving antenna height above ground level is 10 meter.

Figure 3: Antenna height difference corrections, for a horizontal distance range of 0.1‑1.5 km between transmitting and receiving antenna, and for five different transmitting antenna heights above ground level (ha), where receiving antenna height above ground level is 10 meter.

Correction for short paths in urban and suburban environments have been removed (Removed)

Correction for short paths in urban and suburban environments has been removed in Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. In Figure 4 the correction for short urban and suburban paths is presented for a horizontal distance range of 0.1‑14.9 km, at a frequency of 600 MHz, for three different transmitting antenna heights above ground level, and where ground cover surrounding receiving antenna is 10 meter.

Figure 4: Correction for short urban and suburban paths at a frequency of 600 MHz, for three different transmitting antenna heights above ground level (ha), where ground cover surrounding receiving antenna is 10 meter.

–

Thank you for reading this article regarding Four (4) Important News in Rec. ITU‑R P.1546‑5. Please share and comment. All feedback is welcome!

Why the Choice of T2-Frame Length is Essential for DVB-T2

Posted on November 11, 2013 Leave a Comment

You want to use optimal DVB-T2 system parameters. Here’s why the choice of T2-Frame length is important.

Before diving into the details of T2-Frame length, let’s directly give the answer to the why in the headline – the choice of frame length is important if one want to optimize the bit rate and the interleaving depth.

The T2-Frame length, or frame duration, depends on the FFT size, guard interval, and number of OFDM data symbols. It’s a configurable parameter and is limited to a maximum value of 250 milliseconds.

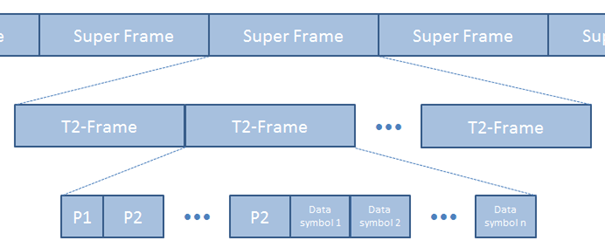

To understand how the frame length affects the capacity and interleaving depth we have to look at the anatomy of the DVB-T2 signal. The main building block of a DVB-T2 system is called a Super Frame and consists of a number of T2-Frames, where each T2-Frame in turn consists of a number of OFDM symbols. The purpose of T2-Frames is to carry the DVB-T2 services and related signaling. Every T2-frame starts with the preamble symbols P1 and P2. The T2-frame always starts with one P1 symbol which is used for synchronization and frame detection. The P1 symbol is then followed by at least one P2 symbol that is used for signaling and data transmission. The number of P2 symbols depends on the selected FFT size. The remainder of the T2-frame consists of a configurable number of data symbols that are used to carry the data. The main building blocks of the physical frame structure for DVB-T2 are presented in the figure below.

One can easily believe that a longer T2-frame length always will result in an increase of total bit rate due to the fact of the overhead associated with the preamble symbols P1 and P2. But because a T2-frame always contains a whole number of FEC-blocks, the OFDM cells which do not make up a whole FEC-block will be dummy cells, and that will of course result in a loss of capacity. To achieve the highest possible bit rate the number of dummy cells therefore need to be minimized.

A consequence of increasing the number of data symbols is of course that the number of OFDM cells per T2-frame also will increase. Since there is a limitation on the number of OFDM cells that fits within one time interleaving block, there is a point at which increasing the number of data symbols will result in that its OFDM cells must be filled up in one additional time interleaving block. When this happens it will result in a reduction of the time interleaving depth. This is because the OFDM cells are now divided into one additional time interleaving block while the increase of the T2-frame duration is increased only marginally.

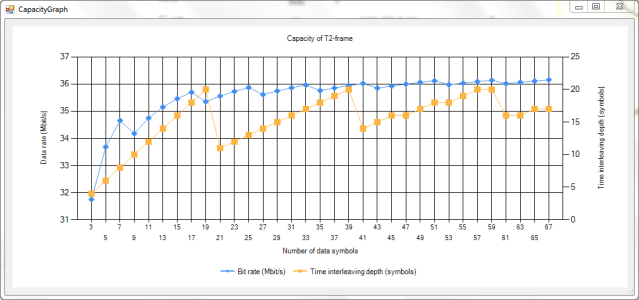

The figure below is a screen shot from PROGIRA® plan where the capacity and interleaving depth graph is presented as a function of the number of used data symbols for the case of FFT size 32K, extended carrier mode, guard-interval fraction 1/128, 256-QAM, code rate 3/5, and the long FECFRAME. In this example it can be seen that the best choice of number of data symbols would be 59. This choice would results in a high bit-rate (about 36 Mbit/s) and a high time interleaving depth (20 symbols).

Screen shot from PROGIRA® plan which presents the capacity and interleaving depth graph for the case of FFT size 32K, extended carrier mode, guard-interval fraction 1/128, 256-QAM, code rate 3/5, and the long FECFRAME.

–

Thank you for reading this article regarding Why the Choice of T2-Frame Length is Essential for DVB-T2. Please share and comment! All feedback is welcome!

DVB-T2 FECFRAME – What is it?

Posted on October 28, 2013 Leave a Comment

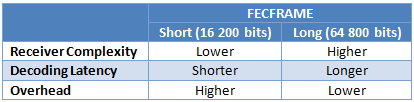

FECFRAME is a fundamental DVB-T2 system parameter. There are two FECFRAME values: long (64 800 bits) and short (16 200 bits).

FEC (Forward Error Correction) is a technique that is used for correcting errors in data transmission over noisy communication channels. The transmitter accomplishes FEC by adding redundant check bits to the input data stream using a certain algorithm. Because of the redundancy the receiver is enabled to detect a limited number of errors that may occur in the received data stream.

The FEC method used in DVB-T2 is a concatenated LDPC (Low-Density Parity-Check) and BCH (Bose-Chaudhuri-Hocquenghem) code.

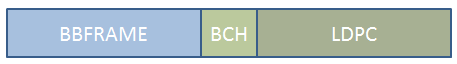

The input to a DVB-T2 system consists of one or more logical data streams. Each data stream is sliced into data fields which are called baseband frames (BBFRAMEs). A FECFRAME consists of a BBFRAME and its redundant check bits – the check bits of the BCH outer code, and the check bits of the LDPC inner code.

The number of bits in the FECFRAME is always constant – 64 800 bits (long) or 16 200 (short). The number of bits in the BBFRAME, BCH, and LDPC field is dependent on the selected code rate. For example, using the long FECFRAME and code rate 3/4, the number of bits in each field is: 48 408 (BBFRAME), 192 (BCH), and 16 200 (LDPC).

In the table below follows a short summary of the pros and cons for long and short FECFRAME.

For more information about the DVB-T2 FECFRAME system parameter, see the following reference: ETSI EN 302 755 V1.3.1 (2012-04). Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Frame structure channel coding and modulation for a second generation digital terrestrial television broadcasting system (DVB-T2).

–

Thank you for reading this article regarding DVB-T2 FECFRAME. If you have any questions about this article do not hesitate to contact me. All feedback is welcome!

An Introduction to the Whats, Whys, and Hows of DVB-T2 Scattered Pilot Patterns

Posted on October 13, 2013 Leave a Comment

Today’s most popular digital wireless systems – for example WLAN, digital terrestrial broadcast systems, 4G cellular networks, etc. – are all based on Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM).

In OFDM a large number of closely spaced orthogonal carriers are used to carry data on several parallel channels. A smaller number of the carriers are allocated to pilot tones which, among other things, can be used to estimate the channel.

The transmission protocol describes when and with what phase positions the pilot tones are transmitted. Based on that information the receiver can continuously estimate the quality of the channel over all frequencies. The performance of channel estimation in OFDM systems depends of course on the density of the predetermined scattered pilot symbols.

DVB-T uses the same static pilot tone pattern for all combinations of system parameters. DVB-T2 is more flexible and there are eight different pilot patterns, PP1-PP8, to select from.

The DVB-T2 scattered pilot pattern should be selected depending on what the expected channel type will be at the receiver. When selecting pilot pattern it is also very important to be aware of the trade-off between capacity and performance.

For a mobile or portable channel, where doppler performance is important, a pattern with a rapid repeat cycle should be selected. If Doppler performance is a dominant factor PP2, PP4 or PP6 should be considered. For those pilot patterns the scattered pilots will be repeated every second OFDM symbol. For PP1, PP3, PP5 and PP7 the scattered pilots will be repeated every fourth OFDM symbol.

If capacity is a dominant factor the least dense patterns should be selected. Pilot patterns with the greatest distances between pilots provide the highest capacity as more carriers are available to carry the data.

Required carrier to noise ratio (CNR) also depends on the selected pilot pattern. A denser pattern requires a higher CNR than those with a lower density. If the CNR is a dominant factor then lower density patterns, such as PP6 and PP7, should be considered.

The density of the scattered pilot patterns for PP2 and PP7 for DVB-T2 in SISO mode are presented in the two figures below.

–

Thank you for reading this article about An Introduction to the Whats, Whys and Hows of DVB-T2 Scattered Pilot Patterns. If you have any questions about this article do not hesitate to contact me. Your feedback is welcome!

DVB-T2 and Large SFNs – Some Pros and Cons

Posted on September 17, 2013 Leave a Comment

DVB-T2 is today by far, the most advanced digital terrestrial television (DTT) system. It is much more flexible, robust, and efficient than any other DTT system. DVB-T2 uses OFDM modulation, and offers a wide range of different modes, making it a very flexible standard.

Due to the multi-path immunity of OFDM, DVB-T2 allows the possibility of single frequency network (SFN) operation. A SFN is a network of synchronized transmitters, both in time and frequency, radiating identical signals. DVB-T2 enables the possibility to build much larger SFNs than what is possible for other DTT systems. For example, using a system bandwidth of 8 MHz, DVB-T allows a maximum transmitter separation distance of 67.2 km while DVB-T2 allows 159.6 km.

Below follows an example where I have used PROGIRA® plan to calculate coverage probability for fixed reception (receiving antenna height is 10 meter above ground) for a fictitious national DVB-T2 SFN in Finland using 36 sites. All sites use the same transmitter configuration: European channel 40 (centre frequency 626 MHz), antenna height 300 meter, and ERP 50 kW. The selected DVB-T2 system parameters are presented in the screen shot below. CRC Predict, a terrain based radio wave propagation model, has been used to calculate the field strength contribution from each transmitter and at each receiving location. Interference, from and to other external transmitters, have not been considered in this study.

Co radio horizon distance for the used transmitter and receiver antenna heights is 84 km. Beyond the radio horizon radio waves in UHF are usually attenuated quickly. Since the ratio of “maximum transmitter separation distance” to “co radio horizon” is about a factor of two (2) (159.6/84 =1.9) there are significant opportunities to create a national SFN without introducing self-interference problems.

Below follows a screen shot from PROGIRA® plan where the coverage probability for fixed reception is presented for a fictitious national DVB-T2 SFN in Finland. The blue colour represents areas where coverage probability is at least 95 %.

It is obvious that it is possible to create really large SFNs using DVB-T2 with the longest guard interval. In this example the distance between the two transmitters that are located farthest from each other is 1 125 km!

Below follows a table that presents how the results would change if we used other guard intervals.

The longest possible guard interval that can be used for the DVB-T system is 224 µs. Using that guard interval length for this national SFN would result in a great coverage reduction – according to the table above the population coverage would drop from 94 to only 38 percent.

It is obvious that SFNs enables the possiblity to use the scarce resource of spectrum more efficiently. But everything in life comes with a price tag attached. Two examples of disadvantages with large SFNs are:

- Large SFN requires a long guard interval that significantly reduces the capacity

- Large SFN limits the possibilities to provide regional services

–

Thank you for reading this article about some pros and cons regarding DVB-T2 and Large SFNs. There are a lot of more information to say about the calculation parameters, methods, and databases that have been used in this example. To restrict the scope of this article I have deliberately not addressed them. If you are interested in more information about the calculations, or if you want to give me feedback and discuss the results, or if you have any other question, do not hesitate to contact me.

Three (3) Types of Reasons to Plan a Broadcast Network

Posted on September 11, 2013 Leave a Comment

Quality Reasons

By a careful network planning, operators can provide their customers a robust and quality assured network. In an early stage, long before deployment of the network, problems can be found and solved.

Economic Reasons

The network must be financially viable. Deployment and operation costs must be weighed against the revenue. By a careful network planning the frequency usage can be minimized, transmitters can be used in the most optimal locations, and the number of transmitters and their powers can be kept as low as possible.

Political Reasons

By a careful planning the limited resource of spectrum is not wasted and the most appropriate frequencies are used to minimize the interference to other existing services.

–

Thank you for reading this article regarding Three (3) Types of Reasons to Plan a Broadcast Network. Please share and comment. Your feedback is welcome!

A Simplified Description of Coverage Probability Calculations for OFDM Systems in Radio Network Planning Software

Posted on September 5, 2013 Leave a Comment

Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) is a technique that is used in many popular wireless communication systems, such as digital terrestrial broadcast systems (DVB-T, DVB-T2, ISDB-T, DTMB, CMMB, T-DAB, T-DMB), wireless LAN, WiMAX, and LTE.

OFDM works very well in radio channels where multipath propagation is particularly noticeable. Multipath propagation generates mainly two effects: intersymbol interference and frequency selective fading. By ensuring that the symbol duration is long enough, and using a guard interval between successive OFDM symbols, the system can handle the intersymbol interference caused by multipath propagation. Since wideband OFDM systems use multiple carrier frequencies, the frequency selective fading degrades only a few of the carriers. The information can then be retrieved by using interleaving and error correcting codes.

The ability of OFDM to overcome interference from multipath propagation enables transmission with multiple transmitters using the same frequency – Single Frequency Networks (SFN).

In a SFN multiple copies of the transmitted signals arrive at the receiving antenna with different amplitudes and delays. Strong diversity gains are then obtained resulting in better coverage and higher spectrum efficiency.

In the receiver the signals are handled differently depending on their relative delay to the FFT synchronisation window. If the relative delay is shorter than the guard interval the signal is considered to be useful. If the relative delay is far outside the guard interval intersymbol interference will occur and the signal is considered to be interfering. If the relative delay is somewhere between the two extremes above the signal is considered to be both useful and interfering.

In addition to the signals originated from the SFN transmitters, interfering signals from other transmitters will also be present at the receiver.

In cellular radio and broadcasting systems, where frequency channels are reused, the carrier-to-noise-and-interference ratio (CNIR) must be determined to be able to calculate the coverage probability. CNIR is the quotient between the sum of useful signal powers and the sum of the receiver noise and interfering signal powers.

In radio network planning software it is not feasibly to calculate the received signals in each location within the area to be considered. The signal strength from each transmitter is estimated by a radio propagation model on a regular grid of points. Usually, this grid will have the same resolution as the terrain databases used by the radio propagation model. As a consequence, each grid point can be seen as an area of corresponding size, for example 50×50 meter. These small areas are called pixels.

Within each pixel the received useful and interfering signals are assumed to be random variables with lognormal distributions. The CNIR ratio is then determined each pixel by doing a summation of random variables. The coverage probability in each pixel is determined by calculating the probability that the CNIR distribution exceeds a system specific planning value.

Below is a coverage probability map in 3D produced by using PROGIRA® plan. Thanks to my colleague Björn Tannersjö for the production of this map.

If you have any questions about Radio Network Planning, OFDM, SFN, Coverage Probability Calculations, or if you have any other questions, don’t hesitate to contact me.

–

Thank you for reading this article regarding Coverage Probability Calculations for OFDM Systems in Radio Network Planning Software. Please share and comment. All feedback is welcome!

Recent Comments